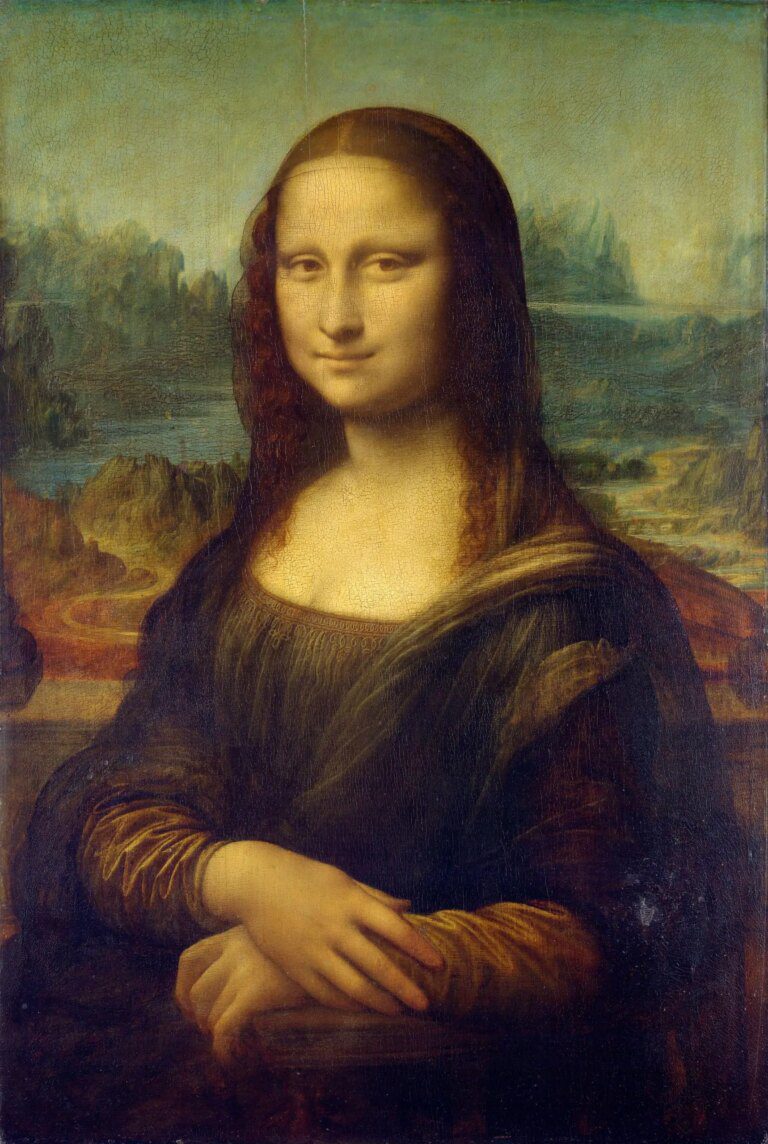

Latest research spotlight Leonardo da Vinci’s experimental use of lead(II) oxide within the foundational layers of his artworks, notably the “Mona Lisa” and “Final Supper,” which presumably performed a job in shaping his iconic masterpieces.

Leonardo da Vinci is famend to at the present time for improvements in fields throughout the humanities and sciences. Now, new analyses printed within the Journal of the American Chemical Society present that his style for experimentation prolonged even to the bottom layers beneath his work. Surprisingly, samples from each the “Mona Lisa” and the “Final Supper” counsel that he experimented with lead(II) oxide, inflicting a uncommon compound referred to as plumbonacrite to kind under his artworks.

The Thriller of da Vinci’s Paints and Pigments

An aura of thriller has surrounded the paints and pigments in da Vinci’s studio, main scientists to scour his writings and paintings to seek for clues. Many work from the early 1500s, together with the “Mona Lisa,” had been painted on wood panels that required a thick, “floor layer” of paint to be laid down earlier than paintings was added. Scientists have discovered that whereas different artists usually used gesso, da Vinci experimented by laying down thick layers of lead white pigment and by infusing his oil with lead(II) oxide, an orange pigment that conferred particular drying properties to the paint above.

This tiny fleck of paint, taken from the “Mona Lisa” is revealing insights into beforehand unknown steps of the artists’ course of. Credit score: Tailored from the Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2023, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c07000

He used an analogous approach on the wall beneath the “Final Supper” — a departure from the normal, fresco approach used on the time. To additional examine these distinctive layers, Victor Gonzalez and colleagues wished to use up to date, high-resolution analytical methods to small samples from these two work.

In-depth Evaluation and Findings

The workforce carried out their analyses on a tiny, “microsample” beforehand obtained from a hidden nook of the “Mona Lisa,” in addition to 17 microsamples obtained from throughout the floor of the “Final Supper.” Utilizing X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy methods, they decided that the bottom layers of those artworks not solely contained oil and lead white, but in addition a a lot rarer lead compound: plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2).

This materials had not beforehand been detected in Italian Renaissance work, although it’d been present in later work by Rembrandt within the 1600s. Plumbonacrite is barely steady beneath alkaline circumstances, suggesting that it fashioned from a response between the oil and lead(II) oxide (PbO). Intact grains of PbO had been additionally present in a lot of the samples taken from the “Final Supper.”

da Vinci’s Unconventional Use of Lead Oxides

Whereas painters had been identified so as to add lead oxides to pigments to assist them dry, the approach has not been proved experimentally for work from da Vinci’s time. In truth, when the researchers searched by means of his writings, the one proof they discovered of PbO was in reference to pores and skin and hair treatments, regardless that it’s now identified to be fairly poisonous. Although he may not have written it down, these outcomes show that lead oxides should have had a spot on the previous grasp’s palette, and may need helped create the masterpieces we all know as we speak.

Reference: “X-ray and Infrared Microanalyses of Mona Lisa’s Floor Layer and Significance Relating to Leonardo da Vinci’s Palette” by Victor Gonzalez, Gilles Wallez, Elisabeth Ravaud, Myriam Eveno, Ida Fazlic, Tiphaine Fabris, Austin Nevin, Thomas Calligaro, Michel Menu, Vincent Delieuvin and Marine Cotte, 11 October 2023, Journal of the American Chemical Society.

DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c07000

The authors acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 analysis and innovation program beneath the Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions.