In some methods, the works have been a type of socially acceptable erotica, offered to bourgeois males who did not dare take part within the lurid night time lifetime of Montmartre themselves, however have been titillated by scenes of it. Made by males for males, the artworks inevitably mirrored the identical obsessions.

Fauvism, with its brash colors and vigorous brush work, might sound rebellious and anti-establishment, however the male artists’ portrayal of ladies perpetuated the identical outdated stereotypes. “They don’t seem to be the loopy anarchists that we are likely to consider they’re,” says Fink. “They have been all petit-bourgeois, they’d households, and so they have been members of the artwork committees of the time.” And because it was predominantly males each creating and shopping for the artwork, he explains, a patriarchal perspective pervaded.

There’s the trope of the feminine as nearer to nature, for instance, with items resembling The Dance by Derain (1906) and Dance by Matisse (1909-10) ascribing ladies with a primitive, naïve high quality. In her 1973 essay Virility and Domination in Early 20th-Century Vanguard Painting, feminist artwork historian Carol Duncan describes “the absoluteness with which ladies have been pushed again to the extremity of the character aspect of the dichotomy, and the insistence with which they have been ranked in whole opposition to all that’s civilised and human”. The “beastliness” of Fauvism clearly prolonged to the illustration of ladies. “A younger lady has younger claws, nicely sharpened,” Matisse as soon as stated.

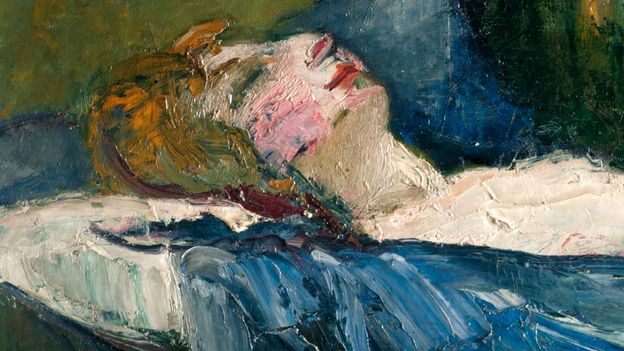

However, says Fink, there’s “a transparent distinction” in the way in which Fauves represented completely different ladies. “They depict their wives in an idolised manner, in a manner, morally superior. They’re dignified of their presence. Whereas, knowledgeable by late Nineteenth-Century discourses, there’s this different excessive, the place lots of the portraits of the Fauves which can be sexual, focus not on the face of the lady, however actually on the flesh, on the genitals, on the breasts. There’s this depiction of a sexual urge for food, of virility, that’s not current in any respect within the household portraits.”

In distinction to his dressed fashions, Matisse’s nudes − resembling Pastoral (1905) and Nude in a Forest (1906) − are typically turned away, faceless and objectified, missing in persona and relegated to traces and curves. Even a nonetheless life, resembling Goldfish and Sculpture (1911), is a living proof. “It is fairly excessive,” agrees Fink. “The buttocks of the lady are enlarged fairly considerably.” The Fauves, conscious of the taboo, argued that they’d a “formal” curiosity in ladies, he says. “However clearly it goes past that.”